The Passenger's Present

The Passenger's Present

The Passenger’s Present proposes a multilayered view of Japanese contemporary society at a time in which the country faces great uncertainty. The work ponders how our imagination can initiate a process, which questions the narratives that surround us and the frameworks that sustain them.

It comprises photographs taken in and around Tokyo, Okinawa and other places since 2013, which are interspersed with constructed still-life images. A sequence of pictures – a kamikaze aircraft, a nuclear reactor, reappearing rainbows, American candy named after the atomic bomb – evokes a web of histories, myths and constructed narratives, which lie beneath the surface of the society.

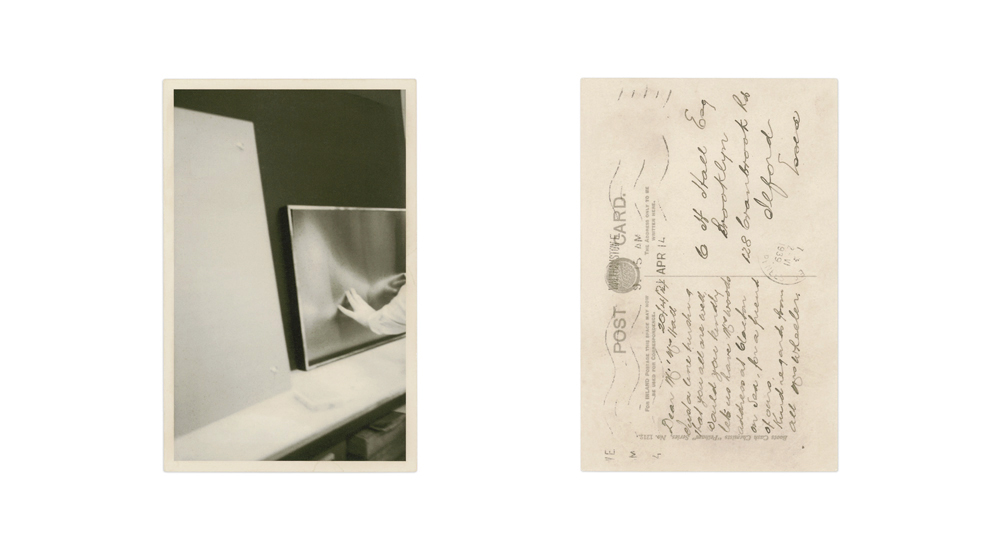

The Passenger’s Present starts with an old photograph of people dancing during a memorial service for the war dead of the Japanese Imperial Army. Above them, the flags of Japan, of the Imperial Army and of the puppet state Manchukuo are visible. This photograph was selected from the author’s grandfather’s photo album, which he made between 1931 and 1945, while he was in Japanese-occupied Northeast China, Manchuria. He once said, “There is nothing to believe anymore”, as if to remind himself. Reviewing this historical period and its legacy, while reflecting on the meaning of these words became an important guide to look at the present and to develop the work.

The Passenger’s Present proposes a multilayered view of Japanese contemporary society at a time in which the country faces great uncertainty. The work ponders how our imagination can initiate a process, which questions the narratives that surround us and the frameworks that sustain them.

It comprises photographs taken in and around Tokyo, Okinawa and other places since 2013, which are interspersed with constructed still-life images. A sequence of pictures – a kamikaze aircraft, a nuclear reactor, reappearing rainbows, American candy named after the atomic bomb – evokes a web of histories, myths and constructed narratives, which lie beneath the surface of the society.

The Passenger’s Present starts with an old photograph of people dancing during a memorial service for the war dead of the Japanese Imperial Army. Above them, the flags of Japan, of the Imperial Army and of the puppet state Manchukuo are visible. This photograph was selected from the author’s grandfather’s photo album, which he made between 1931 and 1945, while he was in Japanese-occupied Northeast China, Manchuria. He once said, “There is nothing to believe anymore”, as if to remind himself. Reviewing this historical period and its legacy, while reflecting on the meaning of these words became an important guide to look at the present and to develop the work.